coreboot 4.14 was released today, on May 10th, 2021.

Since 4.13 there have been 3660 new commits by 215 developers.

Of these, about 50 contributed to coreboot for the first time.

Welcome to the project!

These changes have been all over the place, so that there's no

particular area to focus on when describing this release: We had

improvements to mainboards, to chipsets (including much welcomed

work to open source implementations of what has been blobs before),

to the overall architecture.

Thank you to all developers who made coreboot the great open source

firmware project that it is, and made our code better than ever.

New mainboards

--------------

* AMD Bilby

* AMD Majolica

* GIGABYTE GA-D510UD

* Google Blipper

* Google Brya

* Google Cherry

* Google Collis

* Google Copano

* Google Cozmo

* Google Cret

* Google Drobit

* Google Galtic

* Google Gumboz

* Google Guybrush

* Google Herobrine

* Google Homestar

* Google Katsu

* Google Kracko

* Google Lalala

* Google Makomo

* Google Mancomb

* Google Marzipan

* Google Pirika

* Google Sasuke

* Google Sasukette

* Google Spherion

* Google Storo

* Google Volet

* HP 280 G2

* Intel Alderlake-M RVP

* Intel Alderlake-M RVP with Chrome EC

* Intel Elkhartlake LPDDR4x CRB

* Intel shadowmountain

* Kontron COMe-mAL10

* MSI H81M-P33 (MS-7817 v1.2)

* Pine64 ROCKPro64

* Purism Librem 14

* System76 darp5

* System76 galp3-c

* System76 gaze15

* System76 oryp5

* System76 oryp6

Removed mainboards

------------------

* Google Boldar

* Intel Cannonlake U LPDDR4 RVP

* Intel Cannonlake Y LPDDR4 RVP

Deprecations and incompatible changes

-------------------------------------

### SAR support in VPD for Chrome OS

SAR support in VPD has been deprecated for Chrome OS platforms for > 1

year now. All new Chrome OS platforms have switched to using SAR

tables from CBFS. For the next release, coreboot is updated to align

with the Chrome OS factory changes and hence SAR support in VPD is

deprecated in [CB:51483](https://review.coreboot.org/51483). Starting

with this release, anyone building coreboot for an already released

Chrome OS platform with SAR table in VPD will have to extract the

"wifi_sar" key from VPD and add it as a file to CBFS using following

steps:

* On DUT, read SAR value using `vpd -i RO_VPD -g wifi_sar`

* In coreboot repo, generate CBFS SAR file using:

`echo ${SAR_STRING} > site-local/${BOARD}-sar.hex`

* Add to site-local/Kconfig:

```

config WIFI_SAR_CBFS_FILEPATH

string

default "site-local/${BOARD}-sar.hex"

```

### CBFS stage file format change

[CB:46484](https://review.coreboot.org/46484) changed the in-flash

file format of coreboot stages to prepare for per-file signature

verification. As described in the commit message in more details,

when manipulating stages in a CBFS, the cbfstool build must match the

coreboot image so that they're using the same format: coreboot.rom

and cbfstool must be built from coreboot sources that either both

contain this change or both do not contain this change.

Since stages are usually only handled by the coreboot build system

which builds its own cbfstool (and therefore it always matches

coreboot.rom) this shouldn't be a concern in the vast majority of

scenarios.

Significant changes

-------------------

### AMD SoC cleanup and initial Cezanne APU support

There's initial support for the AMD Cezanne APUs in the tree. This code

hasn't started as a copy of the previous generation, but was based on a

slightly modified version of the example/min86 SoC. During the cleanup

of the existing Picasso SoC code the common parts of the code were

moved to the common AMD SoC code, so that they could be used by the

Cezanne code instead of adding another slightly different copy.

### X86 bootblock layout

The static size C_ENV_BOOTBLOCK_SIZE was mostly dropped in favor of

dynamically allocating the stage size; the Kconfig is still available

to use as a fixed size and to enforce a maximum for selected chipsets.

Linker sections are now top-aligned for a reduced flash footprint and to

maintain the requirements of near jump from reset vector.

### ACPI GNVS framework

SMI handlers for APM_CNT_GNVS_UDPATE were dropped; GNVS pointer to SMM is

now passed from within SMM_MODULE_LOADER. Allocation and initialisations

for common ACPI GNVS table entries were largely moved to one centralized

implementation.

### Intel Xeon Scalable Processor support is now considered mature

Intel Xeon Scalable Processor (Xeon-SP) family [1] is designed

primarily to serve the needs of the server market.

coreboot support for Xeon-SP is in src/soc/intel/xeon_sp directory.

This release has support for SkyLake-SP (SKX-SP) which is the 2nd

generation, and for CooperLake-SP (CPX-SP) which is the 3rd generation

or the latest generation [2] on market.

With this release, the codebase for multiple generations of Xeon-SP

were unified and optimized:

* SKX-SP SoC code is used in OCP TiogaPass mainboard [3]. Support for

this board is in Proof Of Concept Status.

* CPX-SP SoC code is used in OCP DeltaLake mainboard. Support for

this board is in DVT (Design Validation Test) exit equivalent status.

Features supported, (performance/stability) test scopes, known issues,

features gaps are described in [4].

[1] https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/products/details/processors/xeon/scalable.html

[2] https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/products/docs/processors/xeon/3rd-gen-xeon-scalable-processors-brief.html

[3] ../mainboard/ocp/tiogapass.md

[4] ../mainboard/ocp/deltalake.md

Category: coreboot

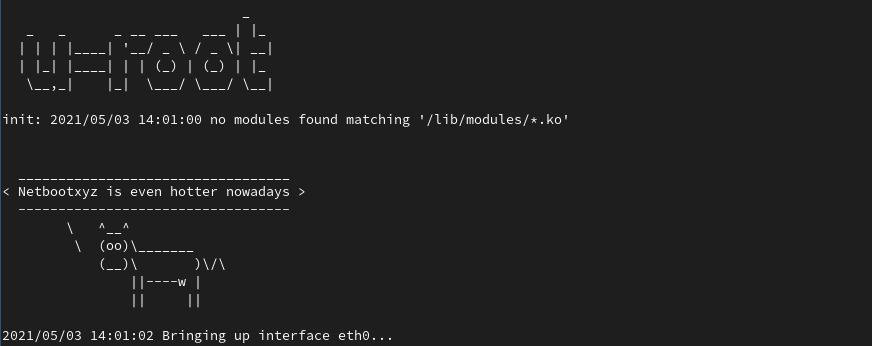

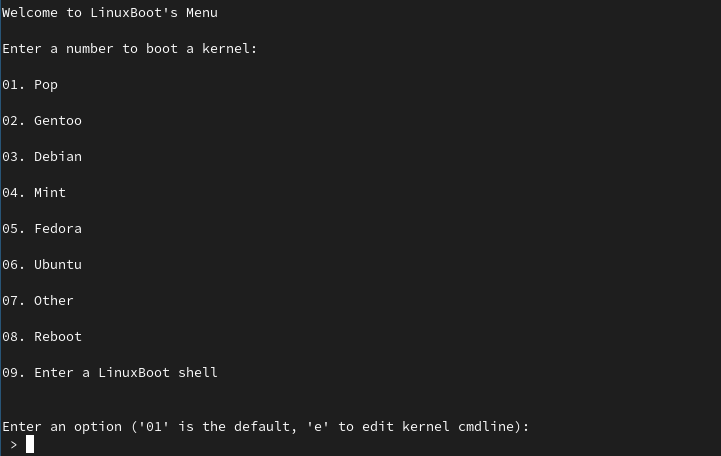

Netboot.xyz is now Part of LinuxBoot

We recently worked on some patches to adopt netboot.xyz and integrate it into LinuxBoot - and it got merged now.

We recently worked on some patches to adopt netboot.xyz and integrate it into LinuxBoot - and it got merged now.

Netboot.xyz

So - what is netboot.xyz? From there website:netboot.xyz is a way to PXE boot various operating system installers or utilities from one place within the BIOS without the need of having to go retrieve the media to run the tool.In our last blog article we already pointed out some development work and what motivated us - basically we need a reliable way to install operating systems on machines sitting either somewhere in a rack not accessible for us, or which do not have any external USB ports. Our former way was to build a busybox image which downloads a disk image containing a minimal Linux operation system into the RAM. Once downloaded we would

dd the image on a hard drive - and off you go.

However that approach needed a lot of manual tooling and adjustment to the current platform we are working on - and netboot.xyz already has a process in place - so adopting this to u-root only seems logical. It's open-source, that's the idea right?

netboot.xyz Image Generation Process

netboot.xyz already has an image processing and generation process in place which we will use to download the images from u-root.

endpoints.yaml file does contain kernel, initrd and squashfs locations in the following manner:

ubuntu-19.10-live-kernel:

path: /ubuntu-core-19.10/releases/download/19.10-055f9330/

files:

- initrd

- vmlinuz

os: ubuntu

version: '19.10'

[...]

ubuntu-19.10-KDE-squash:

path: /ubuntu-squash/releases/download/9854741e-b243fefb/

files:

- filesystem.squashfs

os: ubuntu

version: '19.10'

flavor: KDE

kernel: ubuntu-19.10-live-kernel

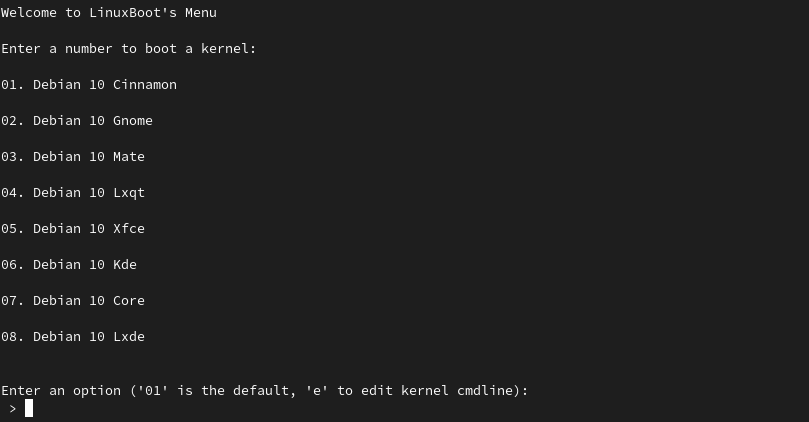

endpoints.yaml file is used to build the u-root netboot.xyz menu:

07 will boot Debian 10 Core.

Be aware - only some major distrobutions have been tested and verified working - Everything in the Other menu can be deemed has experimental and might not work properly.

netboot.xyz provides you a convinent way on how to boot into a live system on your machine. As we are working a lot with server machines where we do not have direct hardware access to, merging netboot.xyz into u-root gives us an easy way to install an operating system on a remote machine during development. If you like to know more about netboot.xyz, check out their homepage. The corresponding code in u-root can be found here. If you like to talk with us about firmware - feel free to contact us!

A short journey to x86 long mode in coreboot on recent Intel platforms

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -M q35 -accel kvm -bios build/coreboot.rom

But, running coreboot's x86_64 code on KVM gave more magic errors than you could find in books about some famous magician with a scarf on his forehead. To summarize:- On recent AMD platforms it stops after entering x86_64 long mode.

- On older Intel platforms everything works.

- On recent Intel platforms after entering long mode every instruction causes a fault, and thus the instruction is emulated by the kernel, which doesn't handle FPU instruction that well...

- On recent Intel platforms the MMU aborts walking page tables and returns the data within the page table itself when looking up some virtual addresses...

coreboot-4.13-241-g52ab788549-dirty Tue Dec 1 18:23:08 UTC 2020 bootblock starting (log level: 7)... CPU: Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E3-1240 v6 @ 3.70GHz CPU: ID 906e9, Kabylake H B0, ucode: 000000d5 CPU: AES supported, TXT supported, VT supported MCH: device id 5918 (rev 05) is Kabylake DT 2 PCH: device id a149 (rev 31) is Skylake PCH-H C236 IGD: device id ffff (rev ff) is Unknown FMAP: Found "FLASH" version 1.1 at 0xb10000. FMAP: base = 0xff000000 size = 0x1000000 #areas = 4 FMAP: area COREBOOT found @ b10200 (5176832 bytes) CBFS: Found 'fallback/romstage' @0x80 size 0xe334 BS: bootblock times (exec / console): total (unknown) / 53 ms

coreboot-4.13-241-g52ab788549-dirty Tue Dec 1 18:23:08 UTC 2020 romstage starting (log level: 7)... pm1_sts: 0900 pm1_en: 4000 pm1_cnt: 00000000 gpe0_sts[0]: 00000000 gpe0_en[0]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[1]: 00000000 gpe0_en[1]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[2]: 00000000 gpe0_en[2]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[3]: 00000000 gpe0_en[3]: 00000000 TCO_STS: 0000 0000 GEN_PMCON: e0810200 000018c8 GBLRST_CAUSE: 00000002 00000000 prev_sleep_state 0 FMAP: area COREBOOT found @ b10200 (5176832 bytes) CBFS: Found 'fspm.bin' @0x5fdc0 size 0x63000 POST: 0x34 FMAP: area RW_MRC_CACHE found @ b00000 (65536 bytes) MRC: no data in 'RW_MRC_CACHE' No memory dimm at address A2 No memory dimm at address A4 POST: 0x36 POST: 0x92 ghost It hung at entering FSP-M, which as it's a binary blob, wasn't automatically recompiled to x86_64. A wrapper (CB:48175) , written in assembly, fixed the problem by falling back to x86_32 when calling into FSP. The wrapper will automatically switch back into x86_64 mode when the function returns. This is slow, but as we don't have proper blobs there's no other way around it. memory init console log:coreboot-4.13-242-g04129be978-dirty Tue Dec 1 18:42:20 UTC 2020 romstage starting (log level: 7)... pm1_sts: 0900 pm1_en: 0000 pm1_cnt: 00000000 gpe0_sts[0]: 00000000 gpe0_en[0]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[1]: 00000000 gpe0_en[1]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[2]: 00000000 gpe0_en[2]: 00000000 gpe0_sts[3]: 00000000 gpe0_en[3]: 00000000 TCO_STS: 0000 0000 GEN_PMCON: e0810200 000018c8 GBLRST_CAUSE: 00000002 00000000 prev_sleep_state 0 FMAP: area COREBOOT found @ b10200 (5176832 bytes) CBFS: Found 'fspm.bin' @0x5fdc0 size 0x63000 POST: 0x34 FMAP: area RW_MRC_CACHE found @ b00000 (65536 bytes) MRC: no data in 'RW_MRC_CACHE' No memory dimm at address A2 No memory dimm at address A4 POST: 0x36 POST: 0x92 POST: 0x98 FspMemoryInit returned 0x80000002 POST: 0xe3 FspMemoryInit returned an error!

The FSP was now able to run, but it returned an error Invalid parameter, which was due to the fact that FSP's config structures contained void pointers, which on x86_64 have a different size and doesn't match what FSP expects. Fixing those headers is an ongoing tasks, but was hacked around. SMM stack trash console log:IOAPIC: Initializing IOAPIC at 0xfec00000 IOAPIC: Bootstrap Processor Local APIC = 0x00 IOAPIC: ID = 0x02 PCI: 00:1f.0 init finished in 9 msecs POST: 0x75 POST: 0x75 PCI: 00:1f.2 init RTC Init Set power on after power failure. Disabling ACPI via APMC.

coreboot-4.13-241-g52ab788549-dirty Tue Dec 1 18:23:08 UTC 2020 smm starting (log level: 7)... SMI_STS: PM1 APM SMI#: ACPI disabled. canary 0xcdcdcdcd7f9ff800 != 0x7f9ff800 SMM Handler caused a stack overflow ghostFinally it booted into SMM, but crashed due to stack trashing. That turned out to be a false positive, as the stack canary is the size of a void pointer and is written in x86_32 assembly, but checked in x86_64 C code and thus failed. Writing 4 additional bytes in assembly code fixed the stack canary check and it finally booted.(CB:48215) patch:/* Write canary to the bottom of the stack */ movl stack_size, %eax subl %eax, %ebx /* %ebx(stack_top) - size = %ebx(stack_bottom) */ movl %ebx, (%ebx) + #if ENV_X86_64 + movl $0, 4(%ebx) + #endif

Summarizing it took about a day to add x86_64 support and half of the code needed to be written in assembly code. With those patches in place it should be easier to port additional platforms to x86_64, reducing the time to a few hours. I invite everyone to play with the changes, hack the code and improve it to make this open source project even more awesome.Announcing coreboot 4.13

coreboot 4.13 was released on November 20th, 2020.

Since 4.12 there were 4200 new commits by over 234 developers. Of these, about 72 contributed to coreboot for the first time.

Thank you to all developers who again helped made coreboot better than ever, and a big welcome to our new contributors!

New mainboards

- Acer G43T-AM3

- AMD Cereme

- Asus A88XM-E FM2+

- Biostar TH61-ITX

- BostenTech GBYT4

- Clevo L140CU/L141CU

- Dell OptiPlex 9010

- Example Min86 (fake board)

- Google Ambassador

- Google Asurada

- Google Berknip

- Google Boldar

- Google Boten

- Google Burnet

- Google Cerise

- Google Coachz

- Google Dalboz

- Google Dauntless

- Google Delbin

- Google Dirinboz

- Google Dooly

- Google Drawcia

- Google Eldrid

- Google Elemi

- Google Esche

- Google Ezkinil

- Google Faffy

- Google Fennel

- Google Genesis

- Google Hayato

- Google Lantis

- Google Lindar

- Google Madoo

- Google Magolor

- Google Metaknight

- Google Morphius

- Google Noibat

- Google Pompom

- Google Shuboz

- Google Stern

- Google Terrador

- Google Todor

- Google Trembyle

- Google Vilboz

- Google Voema

- Google Volteer2

- Google Voxel

- Google Willow

- Google Woomax

- Google Wyvern

- HP EliteBook 2560p

- HP EliteBook Folio 9480m

- HP ProBook 6360b

- Intel Alderlake-P RVP

- Kontron COMe-bSL6

- Lenovo ThinkPad X230s

- Open Compute Project DeltaLake

- Prodrive Hermes

- Purism Librem Mini

- Purism Librem Mini v2

- Siemens Chili

- Supermicro X11SSH-F

- System76 lemp9

Removed mainboards

- Google Cheza

- Google DragonEgg

- Google Ripto

- Google Sushi

- Open Compute Project SonoraPass

Significant changes

Native refcode implementation for Bay Trail

Bay Trail no longer needs a refcode binary to function properly. The refcode was reimplemented as coreboot code, which should be functionally equivalent. Thus, coreboot only needs to run the MRC.bin to successfully boot Bay Trail.

Unusual config files to build test more code

There’s some new highly-unusual config files, whose only purpose is to coerce Jenkins into build-testing several disabled-by-default coreboot config options. This prevents them from silently decaying over time because of build failures.

Initial support for Intel Trusted eXecution Technology

coreboot now supports enabling Intel TXT. Though it’s not feature-complete yet, the code allows successfully launching tboot, a Measured Launch Environment. It was tested on Haswell using an Asrock B85M Pro4 mainboard with TPM 2.0 on LPC. Though support for other platforms is still not ready, it is being worked on. The Haswell MRC.bin needs to be patched so as to enable DPR. Given that the MRC binary cannot be redistributed, the best long-term solution is to replace it.

Hidden PCI devices

This new functionality takes advantage of the existing ‘hidden’ keyword in the devicetree. Since no existing boards were using the keyword, its usage was repurposed to make dealing with some unique PCI devices easier. The particular case here is Intel’s PMC (Power Management Controller). During the FSP-S run, the PMC device is made hidden, meaning that its config space looks as if there is no device there (Vendor ID reads as 0xFFFF_FFFF). However, the device does have fixed resources, both MMIO and I/O. These were previously recorded in different places (MMIO was typically an SA fixed resource, and I/O was treated as an LPC resource). With this change, when a device in the tree is marked as ‘hidden’, it is not probed (pci_probe_dev()) but rather assumed to exist so that its resources can be placed in a more natural location. This also adds the ability for the device to participate in SSDT generation.

Tools for generating SPDs for LP4x memory on TGL and JSL

A set of new tools gen_spd.go and gen_part_id.go are added to automate the process of generating SPDs for LP4x memory and assigning hardware strap IDs for memory parts used on TGL and JSL based boards. The SPD data obtained from memory part vendors has to be massaged to format it correctly as per JEDEC and Intel MRC expectations. These tools take a list of memory parts describing their physical attributes as per their datasheet and convert those attributes into SPD files for the platforms. More details about the tools are added in README.md.

New version of SMM loader

A new version of the SMM loader which accommodates platforms with over 32 CPU threads. The existing version of SMM loader uses a 64K code/data segment and only a limited number of CPU threads can fit into one segment (because of save state, STM, other features, etc). This loader extends beyond the 64K segment to accommodate additional CPUs and in theory allows as many CPU threads as possible limited only by SMRAM space and not by 64K. By default this loader version is disabled. Please see cpu/x86/Kconfig for more info.

Address Sanitizer

coreboot now has an in-built Address Sanitizer, a runtime memory debugger designed to find out-of-bounds access and use-after-scope bugs. It is made available on all x86 platforms in ramstage and on QEMU i440fx, Intel Apollo Lake, and Haswell in romstage. Further, it can be enabled in romstage on other x86 platforms as well. Refer ASan documentation for more info.

Initial support for x86_64

The x86_64 code support has been revived and enabled for QEMU. While it started as PoC and the only supported platform is an emulator, there’s interest in enabling additional platforms. It would allow to access more than 4GiB of memory at runtime and possibly brings optimised code for faster execution times. It still needs changes in assembly, fixed integer to pointer conversions in C, wrappers for blobs, support for running Option ROMs, among other things.

Preparations to minimize enabling PCI bus mastering

For security reasons, bus mastering should be enabled as late as possible. In coreboot, it’s usually not necessary and payloads should only enable it for devices they use. Since not all payloads enable bus mastering properly yet, some Kconfig options were added as an intermediate step to give some sort of “backwards compatibility”, which allow enabling or disabling bus mastering by groups.

Currently available groups are:

- PCI bridges

- Any devices

For now, “Any devices” is enabled by default to keep the traditional behaviour, which also includes all other options. This is currently necessary, for instance, for libpayload-based payloads as the drivers don’t enable bus mastering for PCI bridges.

Exceptional cases, that may still need early bus master enabling in the future, should get their own per-reason Kconfig option. Ideally before the next release.

Early runtime configurability of the console log level

Traditionally, we didn’t allow the log level of the romstage console to be changed at runtime (e.g. via get_option()). It turned out that the technical constraints for this (no global variables in romstage) vanished long ago, though. The new behaviour is to query get_option() now from the second stage that uses the console on. In other words, if the bootblock already enables the console, the romstage log level can be changed via get_option(). Keeping the log level of the first console static ensures that we can see console output even if there’s a bug in the more involved code to query options.

Resource allocator v4

A new revision of resource allocator v4 is now added to coreboot that supports mutiple ranges for allocating resources. Unlike the previous allocator (v3), it does not use the topmost available window for allocation. Instead, it uses the first window within the address space that is available and satisfies the resource request. This allows utilization of the entire available address space and also allows allocation above the 4G boundary. The old resource allocator v3 is still retained for some AMD platforms that do not conform to the requirements of the allocator.

Deprecations

PCI bus master configuration options

In order to minimize the usage of PCI bus mastering, the options we introduced in this release will be dropped in a future release again. For more details, please see Preparations to minimize enabling PCI bus mastering.

Resource allocator v3

Resource allocator v3 is retained in coreboot tree because the following platforms do not conform to the requirements of the resource allocation i.e. not all the fixed resources of the platform are provided during the read_resources() operation:

- northbridge/amd/pi/00630F01

- northbridge/amd/pi/00730F01

- northbridge/amd/pi/00660F01

- northbridge/amd/agesa/family14

- northbridge/amd/agesa/family15tn

- northbridge/amd/agesa/family16kb

In order to have a single unified allocator in coreboot, this notice is being added to ensure that the platforms listed above are fixed before the next release. If there is interest in maintaining support for these platforms beyond the next release, please ensure that the platforms are fixed to conform to the expectations of resource allocation.

[GSoC] libgfxinit: Add support for Bay Trail

Hello everyone. I’ve been working on adding Bay Trail support to libgfxinit as a GSoC project. Yes, as I don’t usually talk much outside of IRC and Gerrit, I would imagine this post would come up as a surprise to most people. Despite the journey being way more difficult than initially foreseen, I eventually managed to get most of what I could test on Bay Trail working, with next to no spaghetti-looking code.

The commits adding Bay Trail support to libgfxinit and integration with coreboot can be retrieved with this Gerrit query. Additionally, the coreboot port for the Asrock Q1900M mainboard used for testing can be found on this Gerrit change.

I ran into several problems while working on this GSoC project, and submitted various fixes and improvements. Links to these commits can be found in later sections. Strictly speaking, these commits are not directly related to this GSoC project, but they spurred when working on GSoC.

Unfortunately, I ran into multiple setbacks, which precluded me from completing everything I had originally planned within the GSoC timeframe:

- Since I only managed to fix some bugs last-minute, the code has not been formally verified yet. Nevertheless, formally verifying the code before it works and has been reviewed is rather pointless, since it needs to be verified again after amending it.

- DisplayPort and integrated panel support could not be tested due to inaccessible hardware. I had to take a plane from the university campus to home on June and it was impossible to squeeze both the Asrock Q1900M and the Asus X551MA in my luggage. I decided to bring the Asrock Q1900M, as it is more compact and easier to work with.

- There was no time left to work on Braswell support. While Bay Trail and Braswell are somewhat related, there are many differences regarding the undocumented parts of the hardware, and there’s even less documentation.

Undeterred by any misfortunes, I am going to finish what I started, come hell or high water.

Project details

libgfxinit is a graphics initialization (aka modesetting) library for embedded environments. It currently supports only Intel hardware, more specifically the Intel Core processor line. It can query and set up most kinds of displays based on their EDID information. You can, however, also specify particular mode lines.

Support for the Intel Bay Trail platform is was missing in libgfxinit. The code hasn’t landed upstream yet, so one would need to fetch it from Gerrit in order to use it. This involves fetching the libgfxinit patches first, using the checkout download option on CB:42359 (the topmost change), and then cherry-picking CB:44071 and CB:44072 into coreboot. CB:44938 and CB:39658 show how to enable libgfxinit for Bay Trail mainboards. Since the available video ports is mainboard-specific, gma-mainboard.ads needs to be adjusted accordingly.

Trials and Tribulations

The hardware is cursed

Getting software to work usually takes some testing, but when said software interacts with hardware, testing becomes essential. And when said hardware is largely undocumented, testing is pretty much the only option. The Display chapters of the graphics programming manuals for these platforms lack the information that matters for libgfxinit. Even the Bay Trail documentation turned out to be incomplete, especially regarding the display PHY and PLL registers. When working on libgfxinit, I soon got Bay Trail to show something on a monitor. However, making that work reliably took much longer than I expected. This was mainly because I needed to spend at least a day or two without looking at the code to see what was wrong with it.

Said PHY and PLL registers are hidden within IOSF-SB, a sideband interconnect network accessed through a mailbox-style interface. To access a register, not only does one need to read or write the register contents, but also needs to program the destination port (address of the hardware block), opcode (which type of read or write) and register offset, and then poll a busy bit until the operation is complete. Of course, this register access mechanism is not described in the graphics documentation, so the only references are existing graphics drivers. Reading someone else’s code in order to understand what documentation should say is, at best, downright painful.

After I managed to get something to show on the screen, I noticed that this would only work on very specific system states. In addition, manually (using the intel_reg utility) writing several undocumented registers before running gfx_test would sometimes help. I eventually figured out that most of the accesses to undocumented registers did not have any effect, because of a blunder in the IOSF accessor library I wrote: I messed up the bitfields when assembling the request register (contains the target port, opcode and some always-one bits), so the accesses would often end up going to the wrong port.

There’s always more bugs

The Bay Trail code in coreboot was only used by a single mainboard: the Google Rambi chromebook/chromebox/chromebase family. Memory initialization is done by a binary-only executable, which contains Intel’s MRC (Memory Reference Code). This binary is simply called “MRC binary” or mrc.bin (the file’s name). However, it is actually an ELF binary, and the Makefile in coreboot will place it at a different offset depending on the file extension. So, Bay Trail has a mrc.elf instead: using the mrc.bin name will place the binary at the wrong offset, and won’t work.

Once this mystery was solved, the MRC on the Asrock Q1900M would not detect any DIMMs. Turns out SMBus support in MRC is broken, so one needs to read the SPD contents into a buffer, and then pass that buffer to the MRC. CB:44092 takes care of that.

Even then, MRC would still refuse to work on the Asrock Q1900M. After some digging, it is because it checks the memory type in the SPD, and bails out if they are not SO-DIMMs or do not support 1.35V operation. The Asrock Q1900M uses full-size desktop UDIMMs, which may not always support 1.35V operation. CB:39568 patches the necessary values in the SPD buffer so that MRC will function as intended.

Externally-induced translocation

I don’t mind running errands or going out in general. However, I do utterly despise having to move and live elsewhere: I have to pack my computers and parts, and I have lots of them. I live in an archipelago, I don’t have my own house nor car yet, and my parents’ home and the university campus aren’t on the same island. Dad usually comes with his car at the start/end of the school year, as I need to move lots of stuff. Oh, and my parents are divorced, so my sister and I go back and forth when not abroad.

Because of the coronavirus outbreak, in-person lessons were suspended for the rest of the academic year. Most people living in the university campus (there’s a students’ residence in there) went back home almost immediately. I didn’t, because I didn’t feel like taking a plane amidst the outbreak and preferred to stay in my cozy server dorm room. However, as there were no more in-person lessons, the residence had to close, and I eventually had to leave. Moreover, Dad couldn’t come this time because he was overwhelmed by work (he was unable to work during lockdown, so everything piled up until the lockdown ended). So, I had to take a plane and leave most of my stuff in the residence, including all of my monitors with digital inputs and one of my two Bay Trail machines, which I had planned on using for GSoC.

And if that wasn’t enough, I’ve had to pack my things again, every week. This means each week only had six useful days, at best. This, plus everything else going on at home, quickly burned me up. It reached a point where I couldn’t bear any longer and had to take a two-week break from coreboot development.

Conclusion

Although there were many unforeseen hurdles and problems around every corner, I would still call this a huge success. Just like university assignments, it has been rushed down to the last minute.

[GSoC] Address Sanitizer, Wrap-up

Hello everyone. The coding period for GSoC 2020 is now officially over and it’s time for the final evaluation. I’ll use this blog post to summarize the project details, illustrate the instructions to use ASan, and discuss some ideas on what can be done further to enhance this feature.

You can find the complete list of commits I made during GSoC with this Gerrit query.

Project details

Memory safety is hard to achieve. We, as humans, are bound to make mistakes in our code. While it may be straightforward to detect memory corruption bugs in few lines of code, it becomes quite challenging to find those bugs in a massive code. In such cases, ‘Address Sanitizer’ may prove to be useful and could help save time.

Address Sanitizer, also known as ASan, is a runtime memory debugger designed to find out-of-bounds accesses and use-after-scope bugs. Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been working to add support for ASan to coreboot. You can read my previous blog posts (Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3) to see my progress throughout the summer.

Here is a description of the components included in the project:

GCC patch

The design of ASan in coreboot is based on its implementation in Linux kernel, also known as Kernel Address Sanitizer (KASAN). However, we can’t directly port the code from Linux.

Unlike the Linux kernel which has a static shadow region layout, we have multiple stages in coreboot and thus require a different shadow offset address. Unfortunately, GCC currently only supports adding a static shadow offset at compile time using -fasan-shadow-offset flag. Therefore the foremost task was to add support for dynamic shadow offset to GCC.

We enabled GCC to determine the shadow offset address at runtime using a callback function named __asan_shadow_offset. This supersedes the need to specify this address at compile time. GCC then makes use of this shadow offset in its internal mem_to_shadow translation function to poison stack variables’ redzones.

The patch further allowed us to place the shadow region in a separate linker section. This ensured if a platform didn’t have enough memory space to hold the shadow buffer, the build would fail.

The way the patch was introduced to GCC’s code base ensures that if

one compiles a piece of code with the new switch enabled i.e. --param asan-use-shadow-offset-callback=1 but has not applied the patch itself to GCC, the compiler will throw the following error because the newly introduced switch is unknown for an out of box GCC: invalid --param name 'asan-use-shadow-offset-callback‘.

I believe this patch might also be useful to the developers who contribute to other open-source projects. Hence, I’ve put this patch on GCC’s mailing list and asked GCC’s developers to include this feature in their upcoming release.

ASan in ramstage

Since ramstage uses DRAM, regardless of the platform, it should always have enough room in the memory to hold the shadow buffer. Therefore, I began by adding support for ASan in ramstage on x86 architecture.

To reserve space in memory for the shadow region, I created a separate linker section and named it asan_shadow. Here, instead of allocating shadow memory for the whole memory region which includes drivers and hardware mapped addresses, I only defined shadow region for the data and heap sections.

Then I started porting KASAN library functions, tweaking them to make them suitable for coreboot.

The next task was to initialize the shadow memory at runtime. I created a function called asan_init which unpoisons i.e. sets the shadow memory corresponding to the addresses in the data and heap sections to zero.

In the case of global variables, instead of poisoning the redzones directly, the compiler inserts constructors invoking the library function named __asan_register_globals to populate the relevant shadow memory regions. So, I wrote a function named asan_ctors which calls these constructors at runtime and added a call to this function to asan_init().

After doing some tests, I realized that compiler’s ASan instrumentation cannot insert asan_load or asan_store state checks in the memory functions like memset, memmove and memcpy as they are written in assembly. So, I added manual checks using the library function named check_memory_region for both source and destination pointers.

ASan in romstage

Once I had ASan in ramstage working as expected, I started adding support for ASan to romstage.

It was challenging because of two reasons. First, even within the same architecture, the size of L1 cache varies across the platforms from 32KB in Braswell to 80KB in Ice Lake and thus we can’t enable ASan in romstage for all platforms by doing tests on a handful of devices. Second, the size of a cache is very small compared to RAM making it difficult to fit asan_shadow section in the limited memory.

Thankfully, the latter issue, to a large extent, was solved by our GCC patch which allowed us to append asan_shadow section to the region already occupied by the coreboot program and make efficient use of limited memory.

Now to resolve the first issue, I introduced a Kconfig option called HAVE_ASAN_IN_ROMSTAGE to denote if a particular platform supports ASan in romstage. This allowed us to enable ASan in romstage only for the platforms which have been tested.

Based on the hardware available with me and my mentor, I enabled ASan in romstage for Haswell and Apollo Lake platforms, apart from QEMU.

Project usage

Instructions for how to use ASan are included in ASan documentation. I’ll restate them with an example here.

Suppose there is a stack-out-of-bounds error in cbfs.c that we aren’t aware of. Let’s see if ASan can help us detect it.

int cbfs_boot_region_device(struct region_device *rdev)

{

int stack_array[5], i;

boot_device_init();

for (i = 10; i > 0; i--)

stack_array[i] = i;

return vboot_locate_cbfs(rdev) &&

fmap_locate_area_as_rdev("COREBOOT", rdev);

}First, we have to enable ASan from the configuration menu. Just select Address sanitizer support from General setup menu. Now, build coreboot and run the image.

ASan will report the following error in the console log:

ASan: stack-out-of-bounds in 0x7f7432fd

Write of 4 bytes at addr 0x7f7c2ac8Here 0x7f7432fd is the address of the last good instruction before the bad access. In coreboot, stages are relocated. So, we have to normalize this address to find the instruction which causes this error.

For this, let’s subtract the start address of the stage i.e. 0x7f72c000. The difference we get is 0x000172fd. As per our console log, this error happened in the ramstage. So, let’s look at the sections headers of ramstage from ramstage.debug.

$ objdump -h build/cbfs/fallback/ramstage.debug

build/cbfs/fallback/ramstage.debug: file format elf32-i386

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA LMA File off Algn

0 .text 00070b20 00e00000 00e00000 00001000 2**12

CONTENTS, ALLOC, LOAD, RELOC, READONLY, CODE

1 .ctors 0000036c 00e70b20 00e70b20 00071b20 2**2

CONTENTS, ALLOC, LOAD, RELOC, DATA

2 .data 0001c8f4 00e70e8c 00e70e8c 00071e8c 2**2

CONTENTS, ALLOC, LOAD, RELOC, DATA

3 .bss 00012940 00e8d780 00e8d780 0008e780 2**7

ALLOC

4 .heap 00004000 00ea00c0 00ea00c0 0008e780 2**0

ALLOCHere the offset of the text segment is 0x00e00000. Let’s add this offset to the difference we calculated earlier. The resultant address is 0x00e172fd.

Next, we read the contents of the symbol table and search for a function having an address closest to 0x00e172fd.

$ nm -n build/cbfs/fallback/ramstage.debug

........

........

00e17116 t _GLOBAL__sub_I_65535_1_gfx_get_init_done

00e17129 t tohex16

00e171db T cbfs_load_and_decompress

00e1729b T cbfs_boot_region_device

00e17387 T cbfs_boot_locate

00e1740d T cbfs_boot_map_with_leak

00e174ef T cbfs_boot_map_optionrom

........The symbol having an address closest to 0x00e172fd is cbfs_boot_region_device and its address is 0x00e1729b. This is the function in which our memory bug is present.

Now, as we know the affected function, we read the assembly contents of cbfs_boot_region_device which is present in cbfs.o to find the faulty instruction.

$ objdump -d build/ramstage/lib/cbfs.o

........

........

51: e8 fc ff ff ff call 52 <cbfs_boot_region_device+0x52>

56: 83 ec 0c sub $0xc,%esp

59: 57 push %edi

5a: 83 ef 04 sub $0x4,%edi

5d: e8 fc ff ff ff call 5e <cbfs_boot_region_device+0x5e>

62: 83 c4 10 add $0x10,%esp

65: 89 5f 04 mov %ebx,0x4(%edi)

68: 4b dec %ebx

69: 75 eb jne 56 <cbfs_boot_region_device+0x56>

........Let’s look for the last good instruction before the error happens. It would be the one present at the offset 62 (0x00e172fd – 0x00e1729b).

The instruction is add $0x10,%esp and it corresponds to for (i = 10; i > 0; i--) in our code. It means the very next instruction i.e. mov %ebx,0x4(%edi) is the one that causes the error. Now, if you look at C code of cbfs_boot_region_device() again, you’ll find that this instruction corresponds to stack_array[i] = i.

Voilà! we just caught the memory bug using ASan.

Future work

While my work for GSoC 2020 is complete, I think the following extensions would be useful for this project:

Heap buffer overflow

Presently, ASan doesn’t detect out-of-bounds accesses for the objects defined in heap. Fortunately, the support for these types of memory bugs can be added easily.

We just have to make sure that whenever some block of memory is allocated in the heap, the surrounding areas (redzones) are poisoned. Correspondingly, these redzones should be unpoisoned when the memory block is de-allocated.

Post-processing script

Unlike Linux, coreboot doesn’t have %pS printk format to dereference a pointer to its symbolic name. Therefore, we normalize the pointer address manually as I showed above to determine the name of the affected function and further use it to find the instruction which causes the error.

A custom script can be written to automate this process.

Support for other platforms and architectures

Jenkins builder built successfully for all x86 boards except for the ones that hold either Braswell SoC or i440bx northbridge where the cache area got full and thus couldn’t fit the asan_shadow section. It shows that support for ASan in romstage can be easily added to most x86 platforms. We just have to test them by selecting HAVE_ASAN_IN_ROMSTAGE option and resolve the compilation errors if any.

Enabling ASan in ramstage on other architectures like ARM or RISC-V should be easy too. We just have to make sure the shadow memory is initialized as early as possible when ramstage is loaded. This can be done by making a function call to asan_init() at the appropriate place.

Similarly, ASan in romstage can be enabled for other architectures. I have mentioned some key points in ASan documentation which could be used by someone who might be interested in doing so.

For the platforms that don’t have enough space in the cache to hold the asan_shadow section, we have to come up with a new translation function that uses a much compact shadow memory. Since the stack buffers are protected by the compiler, we’ll also have to create another GCC patch forcing it to use the new translation function for this particular platform.

Acknowledgement

I’d like to thank my mentor Werner Zeh for his continued assistance during the past 13 weeks. This project certainly wouldn’t have been possible without his valuable suggestions and the knowledge he shared. I’d also like to thank Patrick Georgi for helping me with the work authorization initially and later supervising my work during the time when Werner was on vacation.

Further, I am grateful to every member of the community for assisting me whenever I got stuck, reviewing my code, reading my blogs, and sharing their feedback.

It has been an amazing journey and I look forward to contributing to coreboot in the future.

[GSoC] Address Sanitizer, Part 3

Hello again! The third and final phase of GSoC is coming to an end and I’m glad that I made it this far. In this blog post, I’d like to outline the work done in the last two weeks.

Memory functions

Compiler’s ASan instrumentation cannot insert asan_load or asan_store memory checks in the memory functions like memset, memmove and memcpy. This is because these functions are written in assembly.

While Linux kernel replaces these functions with their variants which are written in C, I took a different approach.

In coreboot, the assembly instructions for these memory functions are embedded into C code using GNU’s asm extension. This provided me with an opportunity to use the ASan library function named check_memory_region to manually check the memory state before performing each of these operations. At the start of each function, I added the following code snippet:

#if (ENV_ROMSTAGE && CONFIG(ASAN_IN_ROMSTAGE)) || (ENV_RAMSTAGE && CONFIG(ASAN_IN_RAMSTAGE))

check_memory_region((unsigned long)src, n, false, _RET_IP_);

check_memory_region((unsigned long)dest, n, true, _RET_IP_);

#endifThis way neither I had to fiddle with the assembly instructions nor I had to replace these functions with their C variants which might have caused some performance issues. [CB:44307]

Documentation

Since I finished a little early with what I had proposed to deliver, Werner suggested that I should write documentation on ASan and I am happy that he did. When I read the intro of the documentation guidelines, I realized how a feature as significant as ASan might go unnoticed and unused by many if it lacks proper documentation.

In ASan documentation, I have tried my best to answer questions like how to use ASan, what kind of bugs can be detected, what devices are currently supported, and how ASan support can be added to other architectures like ARM or RISC-V.

The documentation is not final yet and I’d really appreciate inputs from the community. So, please give it a read and share your feedback. [CB:44814]

In the end, I’d like to announce that ASan patches have been merged into the coreboot source tree. You can go ahead and make use of this debugging tool to look for memory corruption bugs in your code.

[GSoC] Address Sanitizer, Part 2

Hello again! Its been a month since my last blog post. So, there are many updates I’d like to share. I’ll first cover the Address Sanitizer (ASan) algorithm in detail and then summarize the progress made until the second evaluation period.

If you recall my last post, I had briefly talked about the principle behind ASan. Now, let us discuss the ASan algorithm in much more depth. But first, we need to understand the memory layout and how the compiler’s instrumentation works.

Memory mapping

ASan divides the memory space into 2 disjoint classes:

- Main Memory (mem): This represents the original memory used by our coreboot program in a particular stage.

- Shadow Memory (shadow): This memory region contains the shadow values. The state of each 8 aligned bytes of mem is encoded in a byte in shadow. As a consequence, the size of this region is equal to 1/8th of the size of mem. To reserve a space in memory for this class, we added a new linker section and named it

asan_shadow.

This is how we added asan_shadow in romstage:

#if ENV_ROMSTAGE && CONFIG(ASAN_IN_ROMSTAGE)

_shadow_size = (_ebss - _car_region_start) >> 3;

REGION(asan_shadow, ., _shadow_size, ARCH_POINTER_ALIGN_SIZE)

#endifand in ramstage:

#if ENV_RAMSTAGE && CONFIG(ASAN_IN_RAMSTAGE)

_shadow_size = (_eheap - _data) >> 3;

REGION(asan_shadow, ., _shadow_size, ARCH_POINTER_ALIGN_SIZE)

#endif

The linker symbol pairs (_car_region_start, _ebss) and ( _data, _eheap) are references to the boundary addresses of mem in romstage and ramstage respectively.

Now, there exists a correspondence between mem and shadow classes and we have a function named asan_mem_to_shadow that performs this translation:

void *asan_mem_to_shadow(const void *addr)

{

#if ENV_ROMSTAGE

return (void *)((uintptr_t)&_asan_shadow + (((uintptr_t)addr -

(uintptr_t)&_car_region_start) >> ASAN_SHADOW_SCALE_SHIFT));

#elif ENV_RAMSTAGE

return (void *)((uintptr_t)&_asan_shadow + (((uintptr_t)addr -

(uintptr_t)&_data) >> ASAN_SHADOW_SCALE_SHIFT));

#endif

}

In other words, asan_mem_to_shadow maps each 8 bytes of mem to 1 byte of shadow.

You may wonder what is stored in shadow? Well, there are only 9 possible shadow values for any aligned 8 bytes of mem:

- The shadow value is 0 if all 8 bytes in qword are unpoisoned (i.e. addressable).

- The shadow value is negative if all 8 bytes in qword are poisoned (i.e. not addressable).

- The shadow value is k if the first k bytes are unpoisoned but the rest 8-k bytes are poisoned. Here k could be any integer between 1 and 7 (1 <= k <= 7).

When we say a byte in mem is poisoned, we mean one of these special values are written into the corresponding shadow.

Instrumentation

Compiler’s ASan instrumentation adds a runtime check to every memory instruction in our program i.e. before each memory access of size 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16, a function call to either __asan_load(addr) or __asan_store(addr) is added.

Next, it protects stack variables by inserting gaps around them called ‘redzones’. Let’s look at an example:

int foo ()

{

char a[24] = {0};

int b[2] = {0};

int i;

a[5] = 1;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

b[i] = i;

return a[5] + b[1];

}For this function, the instrumented code will look as follows:

int foo ()

{

char redzone1[32]; // Slot 1, 32-byte aligned

char redzone2[8]; // Slot 2

char a[24] = {0}; // Slot 3

char redzone3[32]; // Slot 4, 32-byte aligned

int redzone4[6]; // Slot 5

int b[2] = {0}; // Slot 6

int redzone5[8]; // Slot 7, 32-byte aligned

int redzone6[7];

int i;

int redzone7[8];

__asan_store1(&a[5]);

a[5] = 1;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

__asan_store4(&b[i]);

b[i] = i;

__asan_load1(&a[5]);

__asan_load4(&b[1]);

return a[5] + b[1];

}As you can see, the compiler has inserted redzones to pad each stack variable. Also, it has inserted function calls to __asan_store and __asan_load before writes and reads respectively.

The shadow memory for this stack layout is going to look like this:

Slot 1: 0xF1F1F1F1

Slots 2, 3: 0xF1000000

Slot 4: 0xF1F1F1F1

Slots 5, 6: 0xF1F1F100

Slot 7: 0xF1F1F1F1Here F1 being a negative value represents that all 8 bytes in qword are poisoned whereas the shadow value of 0 represents that all 8 bytes in qword are accessible. Notice that in the slots 2 and 3, the variable ‘a’ is concatenated with a partial redzone of 8 bytes to make it 32 bytes aligned. Similarly, a partial redzone of 24 bytes is added to pad the variable ‘b’.

The process of protecting global variables is a little different from this. We’ll talk about it later in this blog post.

Now, as we have looked at the memory mapping and the instrumented code, let’s dive into the algorithm.

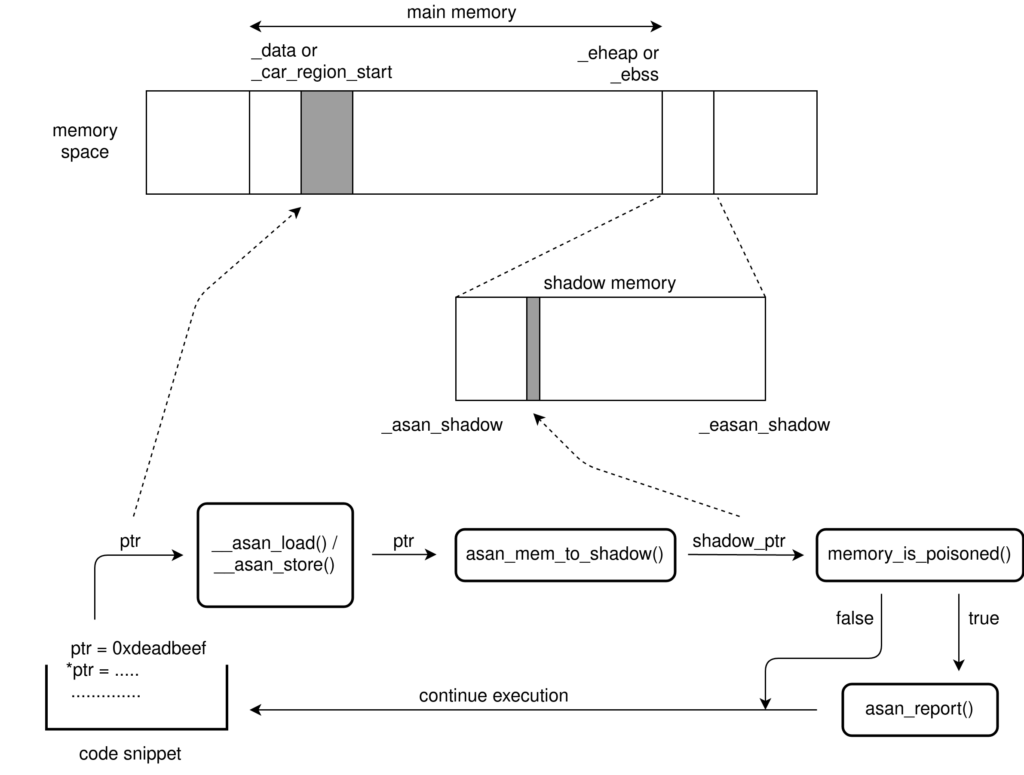

ASan algorithm

The algorithm is pretty simple. For every read and write operation, we do the following:

- First, we find the address of the corresponding shadow memory for the location we are writing to or reading from. This is done by

asan_mem_to_shadow(). - Then we determine if the access is valid based on the state stored in the shadow memory and the size requested. For this, we pass the address returned from

asan_mem_to_shadow()tomemory_is_poisoned(). This function dereferences the shadow pointer to check the memory state. - If the access is not valid, it reports an error in the console mentioning the instruction pointer address, the address where the bug was found, and whether it was read or write. In our ASan library, we have a dedicated function

asan_report()for this. - Finally, we perform the operation (read or write).

- Then, we continue and move over to the next instruction.

Here’s a pictorial representation of the algorithm:

Note that whether access is valid or not, ASan never aborts the current operation. However, the calls to ASan functions do add a performance penalty of about ~1.5x.

Now, as we have understood the algorithm, let’s look at the function foo() again.

int foo ()

{

char a[24] = {0};

int b[2] = {0};

int i;

__asan_store1(&a[5]);

a[5] = 1;

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++)

__asan_store4(&b[i]);

b[i] = i;

__asan_load1(&a[5]);

__asan_load4(&b[1]);

return a[5] + b[1];

}Have a look at the for loop. The array ‘b’ is of length 2 but we are writing to it even beyond index 1.

As the loop is executed for index 2, ASan checks the state of the corresponding shadow memory for &b[2]. Now, let’s look at the shadow memory state for slot 7 again (shown in the previous section). It is 0xF1F1F1F1. So, the shadow value for the location b[2] is F1. It means the address we are trying to access is poisoned and thus ASan is triggered and reports the following error in the console log:

ASan: stack-out-of-bounds in 0x07f7ccb1

Write of 4 bytes at addr 0x07fc8e48Notice that 0x07f7ccb1 is the address where the instruction pointer was pointing to and 0x07fc8e48 is the address of the location b[2].

ASan support for romstage

In the romstage, coreboot uses cache to act as a memory for our stack and heap. This poses a challenge when adding support for ASan to romstage because of two reasons.

First, even within the same architecture, the size of cache varies across the platforms. So, unlike ramstage, we can’t enable ASan in romstage for all platforms by doing tests on a handful of devices. We have to test ASan on each platform before adding this feature. So, we decided to introduce a new Kconfig option HAVE_ASAN_IN_ROMSTAGE to denote if a particular platform supports ASan in romstage. Now, for each platform for which ASan in romstage has been tested, we’ll just select this config option. Similarly, we also introduced HAVE_ASAN_IN_RAMSTAGE to denote if a given platform supports ASan in ramstage.

The second reason is that the size of a cache is very small compared to the RAM. This is critical because the available memory in the cache is quite low. In order to fit the asan_shadow section on as many platforms as possible, we have to make efficient use of the limited memory available. Thankfully, to a large extent, this problem was solved by our GCC patch which allowed us to append the shadow memory buffer to the region already occupied by the coreboot program. (I ran Jenkins builder and it built successfully for all boards except for the ones that hold either Braswell SoC or i440bx northbridge where the cache area got full and thus couldn’t fit the asan_shadow section.)

In the first stage, we have enabled ASan in romstage for QEMU, Haswell and Apollolake platforms as they have been tested.

Further, the results of Jenkins builder indicate that, with the current translation function, the support for ASan in romstage can be added on all x86 platforms except the two mentioned above. Therefore, I’ve asked everyone in the community to participate in the testing of ASan so that this debugging tool can be made available on as many platforms as possible before GSoC ends.

Global variables

When we initially added support for ASan in ramstage, it wasn’t able to detect out-of-bounds bugs in case of global variables. After debugging the code, I found that the redzones for the global variables were not poisoned. So, I went through GCC’s ASan and Linux’s KASAN implementation again and realized that the way in which the compiler protects global variables was very much different from its instrumentation for stack variables.

Instead of padding the global variables directly with redzones, it inserts constructors invoking the library function named __asan_register_globals to populate the relevant shadow memory regions. To this function, compiler also passes an instance of the following type:

struct asan_global {

/* Address of the beginning of the global variable. */

const void *beg;

/* Initial size of the global variable. */

size_t size;

/* Size of the global variable + size of the red zone. This

size is 32 bytes aligned. */

size_t size_with_redzone;

/* Name of the global variable. */

const void *name;

/* Name of the module where the global variable is declared. */

const void *module_name;

/* A pointer to struct that contains source location, could be NULL. */

struct asan_source_location *location;

}

So, to enable the poisoning of global variables’ redzones, I created a function named asan_ctors which calls these constructors at runtime and added it to ASan initialization code for the ramstage.

You may wonder why asan_ctors() is only added to ramstage? This is because the use of global variables is prohibited in coreboot for romstage and thus there is no need to detect global out-of-bounds bugs.

Next steps..

In the third coding period, I’ve started working on adding support for ASan to memory functions like memset, memmove and memcpy. I’ll push the patch on Gerrit pretty soon.

Once, this is done, I’ll start writing documentation on ASan answering questions like how to use ASan, what kind of bugs can be detected, what devices are currently supported, and how ASan support can be added to other architectures like ARM or RISC-V.

[GSoC] Address Sanitizer, Part 1

Hello everyone. My name is Harshit Sharma (hst on IRC). I am working on the project to add the “Address Sanitizer” feature to coreboot as a part of GSoC 2020. Werner Zeh is my mentor for this project and I’d like to thank him for his constant support and valuable suggestions.

It’s been a fun couple of weeks since I started working on this project. Though I found the initial few weeks quite challenging, I am glad that I was able to get past that and learned some amazing stuff I’d cherish for a long time.

Also, being a student, I find it incredible to have got a chance to work with and learn from such passionate, knowledgeable, and helpful people who are always available over IRC to assist.

A few of you may already know about the progress we’ve made through Werner’s message on the mailing list. This is a much comprehensive report on the work we had done prior to the first evaluation period.

What is Address Sanitizer ?

Address Sanitizer (ASan) is a runtime memory debugging tool, designed to find out of bounds and use after free memory bugs. It is a part of toolset Google has developed which also includes Undefined Behaviour Sanitizer (UBSan), a Thread Sanitizer (TSan), and a Leak Sanitizer (LSan).

This tool would help in improving code quality and thus would make our runtime code more robust.

Compile with ASan

The firstmost task was to ensure that coreboot compiles without any errors after Asan is enabled. For this, we created dummy functions and added the relevant GCC flags to build coreboot with ASan. We also introduced a Kconfig option (currently only available on x86 architecture) to enable this feature. (Patch [1])

Porting code from Linux

The design of ASan in coreboot is based on its implementation in Linux kernel, also known as Kernel Address Sanitizer (KASAN). However, coreboot differs a lot from Linux kernel due to multiple stages and that is what poses a challenge.

Design of ASan

ASan uses compile-time instrumentation that adds a run-time check before every memory instructions.

The basic idea is to encode the state of each 8 aligned bytes of memory in a byte in the shadow region. As a consequence, the shadow memory is allocated to 1/8th of the available memory. The instrumentation of the compiler adds __asan_load and __asan_store function calls before memory accesses which seeks the address of the corresponding shadow memory and then decides if access is legitimate depending on the stored state.

If the access is not valid, it throws an error telling the instruction pointer address, the address where a bug is found and whether it was read or write.

Need for GCC patch

Unlike Linux kernel which has a static shadow memory layout, coreboot has multiple stages with very different memory maps. Thus we require different shadow offset addresses for each stage.

Unfortunately, GCC presently, only supports using a static shadow offset address which is specified at compile time using -fasan-shadow-offset flag.

So, we came up with a GCC patch that introduces a feature to use a dynamic shadow offset address. Through this, we enable GCC to determine shadow offset address at runtime using a callback function __asan_shadow_offset().

Though we’ve presented our patch to GCC developers to convince them to include this change in their upcoming version, for now, ASan on coreboot only works if this patch is applied. (Patches [2] and [3])

Allocating and initializing shadow buffer

Instead of allocating a shadow buffer for the whole memory region, we decided to only define shadow memory for data and heap sections. Since we don’t want to run ASan for hardware mapped addresses, this way we save a lot of memory space.

Once the shadow region is allocated by the linker, the next task is to initialize it as early as possible at runtime. This is done by a call to asan_init() which unpoisons i.e. sets the shadow memory corresponding to the addresses in the data and heap sections to zero.

ASan support for ramstage

We decided to begin in a comparatively simpler stage i.e. ramstage. Since ramstage uses DRAM, the implementation is common across all platforms of a particular architecture. Moreover, ramstage provides enough room in the memory to place our shadow region.

For now, we have only enabled this feature for x86 architecture and it is able to detect stack out of bounds and use after scope bugs. Though the patches are still in the review stage, we did a test on QEMU and siemens mc_apl3 (Apollo Lake based) and so far it looks good to us. (Patch [4])

Next steps..

In the second coding period, we’ve started working on adding ASan to romstage. I will push a change on Gerrit once we make some considerable progress.

We further encourage everyone in the community to review the patches and test this feature on their hardware for better test coverage. The more feedback we get, the more are the chances to have a high-quality debugging tool.

Announcing coreboot 4.12

coreboot 4.12 was released on May 12th, 2020.

Since 4.11 there were 2692 new commits by over 190 developers and of these, 59 contributed for the first time, which is quite an amazing increase.

Thank you to all developers who again helped made coreboot better than ever, and a big welcome to our new contributors!

Maintainers

This release saw some activity on the MAINTAINERS file, showing more persons, teams and companies declare publicly that they intend to take care of mainboards and subsystems.

To all new maintainers, thanks a lot!

Documentation

Our documentation efforts in the code tree are picking up steam, with some 70 commits in that general area. Everything from typo fixes to documenting mainboard support or coreboot APIs.

There’s still room to improve, but the contributions are getting more and better.

Hardware support

The removals due to the announced deprecations as well as the deduplication of boards into variants skew the stats a bit, so at a top level view this is a rare coreboot release in that it removes more boards (51) than it adds (49).

After accounting for the variant moves the numbers in favor of more hardware supported than the previous version. Besides a whole lot of Chrome OS devices (again), this release features a whole bunch of retrofits for devices originally shipping with non-coreboot OEM firmware, but also support for devices that come with coreboot right out of the box.

For that, a shout out to System76, Protectli, Libretrend and the Open Compute Project!

Cleanup

We simplified the header that comes at the top of every file: Instead of a lengthy reference to the license any given file is under, or even the license text itself, we opted for simple SPDX identifiers.

Since people also handled copyright lines differently, we now opt for collecting authors in AUTHORS and let git history tell the whole story.

While at it, the content-free "This file is part of this-and-that project" header was also dropped.

Besides that, there has also been more work to sort out the headers we include across the tree to minimize the code impacting every compilation unit.

Now that our board-variant mechanism matured, many boards that were individual models so far were converted into variants, making it easier to maintain families of devices.

Deprecations

For the 4.12 release a few features on x86 became mandatory. These are relocatable ramstage, postcar stage and C_ENVIRONMENT_BOOTBLOCK.

Relocatable ramstage

Relocatable stages are a feature implemented only on x86, where stages can be relocated at runtime. This is used to place ramstage in a better location that does not collide with memory the OS or the payload tends to use. The rationale behind making this mandatory is that you always want cbmem to be cached so it’s a good location to run ramstage from. It avoids using lower memory altogether so the OS can make use of it and no backing up needs to happen on S3 resume.

Postcar stage

With Postcar stage tearing down Cache-as-Ram is done in a separate stage. This means that romstage has a clean program boundary and that all variables in romstage can be accessed via their linked addresses without runtime resolution. There is no need to link global and static variables via the CAR_GLOBAL macro and no need to access them with car_set/get_var/ptr functions.

C_ENVIRONMENT_BOOTBLOCK

Historically the bootblock on x86 platforms has been compiled with romcc. This means that the generated code only uses CPU registers and therefore no stack. This 20K+ LOC compiler is limited and hard to maintain and so is the code that one has to write in that environment. A different solution is to set up Cache-as-Ram in the bootblock and run GCC compiled code in the bootblock. The advantages are increased flexibility and consistency with other architectures as well as other stages: e.g. printing to console is possible and VBOOT can run before romstage, making romstage updatable via RW FMAP regions.

Platforms dropped from master

The following platforms did not implement those feature are dropped from master to allow the master branch to move on:

- AMDFAM10

- all FSP1.0 platforms: BROADWELL_DE, FSP_BAYTRAIL, RANGELEY

- VIA VX900

In particular on FSP1.0 it is impossible to implement POSTCAR stage. The reason is that FSP1.0 relocates the CAR region to the HOB before returning to coreboot. This means that after FSP returns to coreboot accessing variables via their original address is not possible. One way of obtaining that behavior would be to set up Cache-as-Ram again (but with open source code) and copy the relocated data from the HOB there. This solution is deemed too hacky. Maybe a lesson can be learned from this: blobs should not interfere with the execution environment, as this makes proper integration much harder.

4.11_branch

Given that some platforms supported by FSP1.0 are being produced and popular, the 4.11 release was made into a branch in which further development can happen.

Significant changes

SMMSTORE is now production ready

See smmstore for the documentation on the API, but note that there will be an update to it featuring a much-improved but incompatible API.

Unit testing infrastructure

Unit testing of coreboot is now possible in a more structured way, with new

build subsystem and adoption of Cmocka framework. Tree

has new directory tests/, which comprises infrastructure and examples of unit

tests. See

Unit testing coreboot for the

design document.

Final Notes

Your favorite new feature or supported board didn’t make it to the release notes? They’re maintained collaboratively in the coreboot tree, so when you land something noteworthy don’t be shy, contribute to the upcoming release’s document in Documentation/releases!